The History of Pi: How The Number Took Over The World

All the magic behind the incredible number that goes on for infinity.

Not every mathematical constant gets its own day. But then again, not every constant is pi, the incredible and infinite number represented by this symbol: π. Pi Day was introduced in 1988 in San Francisco, when Larry Shaw, the legendary technical curator of the city’s Exploratorium, saw the connection between March 14 (3.14) and pi (3.14159…). Add in the fact that 3/14 is Albert Einstein’s birthday, and you’ve got a ready-made celebration.

Pi seems simple: It’s the ratio of a circle’s circumference to its diameter. Under the surface, though, it’s anything but. The number has an almost mystical property that has led mathematicians down rabbit holes trying to find more digits of pi and also discovering ways in which it intersects with the rest of mathematics. Here are five incredible facts about the magical number in honor of Pi Day.

David Grossman is a staff writer for PopularMechanics.com. He's previously written for The Verge, Rolling Stone, The New Republic and several other publications. He's based out of Brooklyn.

Watch Next

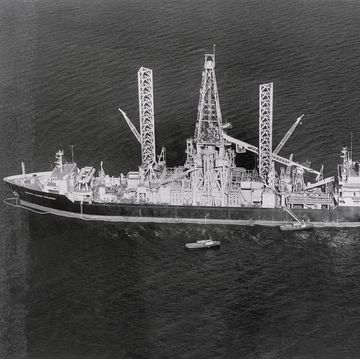

Inside the CIA’s Quest to Steal a Soviet Sub

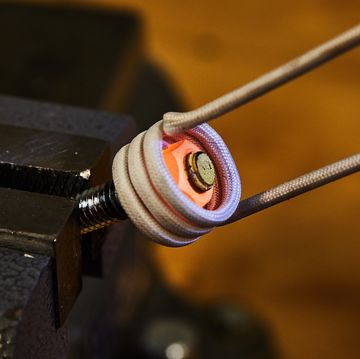

Jumpstart Your Car With a Cordless Tool Battery

Lost Villa of Rome’s Augustus Potentially Found

Could Freezing Your Brain Help You Live Forever?