Alphonse Mucha and Love in the Time of Commercialism

Mucha tried to look to the past and appropriate traditional ideals of love and beauty to the tumultuous era he was living through. He failed

Abigail Leali / MutualArt

Jun 10, 2022

Almost two thousand years ago, in his Sermon on the Mount, Jesus Christ warned those gathered around him: “[W]here your treasure is, there will your heart be also.” The concept is so simple, it is almost tautological: if you value something, you will love it. And yet, history is full of the consequences of individuals and societies whose desires led to their downfall. Whether it was extorting others for pleasure or personal gain, enacting unjust laws to amass power and prestige, lying to achieve false superiority – people have found nearly infinite ways to use and abuse each other in pursuit of their own “treasures.” In a very tangible way, what we love comes to define who we are.

In the modern era, the shockwaves accompanying the Industrial Revolution provide one of the clearest examples of latent desires for wealth and power coming into violent contact with rapidly shifting social realities. Poised between the fall of medieval feudalism and the rise of democracy, many prominent Victorian artists and authors found themselves torn between two very incompatible “treasures.”

Initial of Book of Genesis, Bible of Wenceslas IV, c. 1389

On the one hand was the riches of the Western artistic and philosophical traditions, which feared the consequences of relying on human nature. And, in many ways, the libido dominandi did seem especially overt at the time, with issues such as slavery, child labor, long workdays, philanthropic abuses, and horrific asylums holding a prominent place in political discourse.

On the other hand was the allure of new political philosophies and technological advances, which promised opportunities for human flourishing hitherto unforeseen. To eat, drink, and be merry had never been more accessible nor appeared to have fewer consequences.

But, while today we often look back on Victorian and Edwardian art and architecture as elegant, romantic, and grand, for many at the time it seemed a poor consolation for what had been lost. The tallest buildings, the newest colors, the most unique and innovative styles only papered over the rotting structures of old, failing social and economic systems. Unable to see into the future, many instead focused their efforts at salvaging old systems of ethics, like chivalry, and attempting to redefine them for a new world.

Opening of the Gospel of Matthew, Codex Gigas, 13th c.

Over time, this habit of renewing the old to temper the new worked its way into every area of life. It is especially evident in the work of Czech artist Alphonse Mucha. His advertisements, in particular, feature richly patterned backgrounds, flat compositions, and historical costuming that inevitably call to mind both the expressive poses of Greek painted pottery and the careful detail of medieval illuminated manuscripts.

Alphonse Mucha, Master Jan Hus Preaching at the Bethlehem Chapel - Truth Prevails, No. 8 of The Slav Epic cycle, 1916

In fact, Mucha wanted to be known more as a historical painter than as a designer. While both contemporary and modern viewers identify his graceful women and mesmerizing motifs with the elegance of the Art Nouveau style, Mucha himself saw “Art Nouveau” as a contradiction in terms. Art, he believed, could not be “new.” It could evolve, perhaps, but never be “new.” Seeing the danger in severing art from its historical roots, he instead tried to integrate history into everything he created.

In his historical paintings, like his massive Slav Epic, for instance, as well as his own take on an illuminated manuscript, the Pater Noster, one sees not the hand of an innovator but the heart of a man with a reverence for the past and a devotion to his Catholic faith – albeit infused with more contemporary fascinations with the fantastical, the mystical, and the sensual. Despite his own protests to the contrary, he was in many ways more typical of the period than he may have realized. Hopelessly swept along by the new economic and social structures, he groped blindly through his art for a glimpse of the past in the vastly altered landscape of the present.

Alphonse Mucha, Pater Noster qui es in Coeli, from Le Pater, 1899

Yet the tragedy is that, as with many nineteenth-century creators, in attempting to renew the past for present use, he fundamentally altered its meaning – to dire effect. Where his source materials were meant to inspire devotion, celebrate beauty, examine good and evil, and explore truth, Mucha’s most public works, much as they paid surface-level homage to profound significance, were not destined for such lofty purposes.

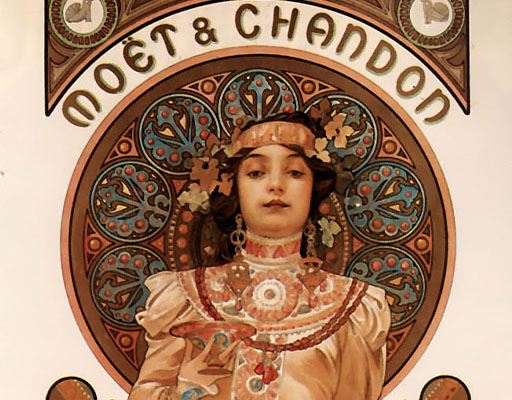

Rather than guiding the public towards a higher good, their goal was to manipulate people’s desires for the benefit of the new industrial elite. His work proves that the contour of a woman or the slightest hint of luxury could translate directly into a theater ticket or a bottle of fine champagne – and another dollar in the pockets of the nouveau riche. In using sacred styles to mask the ugliness of greed and lust for power, Mucha’s advertisements came to perpetuate the burgeoning myth that the artistic, literary, and philosophical ideas of the past were always used as tools for oppression of the poor or to maintain rigid class distinctions. Yet time has shown that, when one takes away beauty in an attempt to achieve justice, it does not solve the real problems of poverty or prejudice. All it accomplishes is to remove the sources of joy and unity that bind people together. Lacking a common love of the true, good, and beautiful, we have fallen not into simple harmony but into radicalization, mental health crises, and increasing socioeconomic inequality.

Alphonse Mucha, Moët & Chandon White Star, 1899

Therefore, while it is difficult to blame Mucha himself for the requirements of his patrons, his advertisements – beautiful and charismatic as they may be – demonstrate the shift that Western society has undergone and continues to undergo. Though the Victorians appropriated beauty to legitimize a culture of consumerism and greed that they believed promised freedom and happiness, it only maintained the poor in their poverty and shackled the wealthy to a life addicted to unfulfilling and hollow pleasures. While previous eras suffered from an inability to produce art on a massive scale, the Victorians instead largely found themselves unable to value art properly at all. In both cases, one could say that the appreciation of beauty is snatched from the hands of the many for the benefit of the few, but in the latter case, it is discarded altogether. Mucha, however unconsciously, seems to have sensed this troubling trend. But what was an artist to do?

Mucha, Moët & Chandon Crémant Impérial, 1899

This is where Mucha and his fellow historians were actually right to look to the past for answers. As Victorian author G.K. Chesterton put it, “Tradition means giving votes to the most obscure of all classes, our ancestors. It is the democracy of the dead. Tradition refuses to submit to the small and arrogant oligarchy of those who merely happen to be walking about.” But to allow what was good about the past to influence us today, we must not, as the Victorians and Edwardians so often did, repurpose it for our own ends. We must acknowledge it on its own terms and learn from it as it is.

It is not enough to build a new art museum modeled on the Parthenon or design a book jacket for a recipe book based on The Last Supper. We know how to use beauty for personal gain; what we have forgotten is how to love it simply because it is beautiful. Superficial mimicry will not help us remember. If we are to truly delight in art again, we must learn to sever our appreciation of beauty from our own desires for wealth, power, or prestige. Only then may we contribute to a world in which our “treasures” need not come at the expense of others’ happiness.

For more on auctions, exhibitions, and current trends, visit our Magazine Page